FAILURES

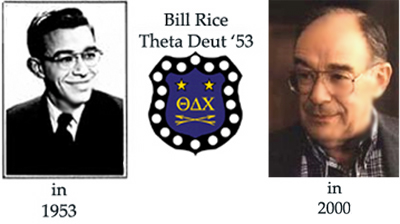

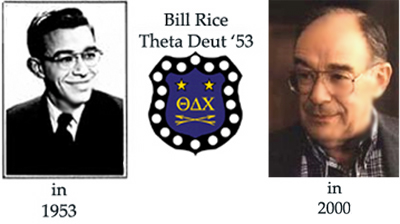

By

William L. R. Rice

Over the years, my career path was

strewn with failures caused by others. While they were not of my

own making, they often had a profound effect on my own career

choices. Some of these failures may be of interest to the

reader.

In March of 1955 I published my

graduate thesis for the USAF Institute of Technology (USAFIT). It

was entitled, “Cation Adsorption on Clay Surfaces”. I had studied

the adsorption of ionized lanthanum on montmorillonite clay. The

study related to the possibility of using clays to decontaminate

nuclear reactor waste products, followed by firing of the clay to make

an impervious body for long term waste disposal. At that time

disposal of radioactive waste was recognized by the industry as a

serious impediment to the use of nuclear power. Although nearly a

half-century has now passed, the US still does not have a permanent

site for disposal of radioactive waste. The Yucca Mountain

facility in Nevada is proposed as a disposal site, but is found

objectionable by many. So the Government has thus far failed in

its statutory responsibility to provide a waste disposal site for the

nuclear industry.

Following graduation from USAFIT,

I was assigned to the Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion (ANP) program.

I managed research contracts to develop radiation resistant fluids and

lubricants for use in the nuclear bomber. The ANP program never

succeeded, because it was not possible to develop materials capable of

withstanding the high temperature and intense nuclear radiation

environment of a nuclear propulsion system. Yet proponents

managed to drag the program out for many years. It took a direct

order by President John F. Kennedy in 1963 to terminate the

program. So this $2 billion program failed. (Although there

was no longer an end use, my modest program did find organic compounds

with resistance to high temperature and nuclear radiation [e.g.

bis(m-phenoxyphenyl) ether].)

I joined the US Atomic Energy

Commission in 1959 and managed research on high temperature nuclear

fuels and materials. During my early years in this capacity, I

was on occasion quite critical of the ANP program, which was still in

existence. Shortly after President Kennedy terminated the

program, my Branch Chief called me into his office and said with a big

smile that he had an additional job for me. With the demise of

ANP, it was decided that the high temperature refractory materials

effort at GE in Cincinnati was to continue for several years, with an

annual budget of about $6 million. This would allow completion of

the ongoing research. I was assigned responsibility for

Headquarters management of the effort! I learned at this point

that being critical can sometimes backfire. This follow-on

research was very successful, but was also classified. Hence the

public had no ready access to the technical results.

One of my responsibilities during

this period was to chair the AEC’s High Temperature Fuels Committee,

where I placed strong emphasis on the reporting of failure. The

most effective way to learn about new fuels is to test them to failure,

to learn use limitations. So when the Committee met, I would

emphasize the importance of good reporting on failures. In fact,

I instituted an award for the best report. At the end of the

three-day meeting, I would announce the winner, who then received a

bottle of Virginia wine. The expense was minor, but the

competition to receive this award became intense!

After various assignments, I

joined the Division of Controlled Thermonuclear Research in 1972.

This Division was responsible for developing a successful fusion

reactor for generation of power. The fusion energy program began

in the early 1950’s, with the stated purpose of attaining controlled

fusion energy in 20 years. For 50 years, success has always

been in the future. In fact, fusion experts now talk about

operating a demonstration fusion power plant in about 35 years, to

enable the commercialization of fusion power. It would appear

that with each year that passes, the goal now slips further into the

future!

Although progress in the fusion

program was limited in the early 1970’s, we actually convinced the

Congressional oversight committees to provide increased funding each

year. The technical criteria for fusion energy success were

presented to the oversight committees on semi-logarithmic paper, which

non-technical members of Congress were unlikely to understand!

What looked like nearness to success on the graphs was no such thing.

The technical data were simply being extrapolated to the next decade on

the log scale and success was still a long way off. But the

members of the committees were impressed and thought that progress was

significant! Despite the expenditure of hundreds of millions of

dollars, the program thus far has failed to meet its original goals.

Shortly after I left the Division,

an avoidable management failure occurred. My former secretary

came to me and told me that she had been asked to resign by her new

boss, solely because she was pregnant. I was amazed by this

action and told her to seek guidance from the Director of

Personnel. As a result, she was reassigned within the Division

with no loss of status and the Division Director had an intense

closed-door training session with the Personnel Director.

The Atomic Energy Commission was

abolished and programs were transferred to the Energy Research and

Development Administration (ERDA) on January 19, 1975. I claim no

responsibility for the termination of the AEC, but I did manage the

farewell party. It was held at the Bureau of Standards cafeteria

in Germantown, MD, and was attended by thousands. As one

benchmark, the group consumed 80 gallons of hard liquor at the four

open bars. The party was a success and only one attendee was

arrested for drunkenness!

In 1975 I became an Assistant

Director of the ERDA Office of Congressional Rela-tions. My

subject areas included solar, geothermal and fusion energy. One

notable failure in this period was the solar energy program. The

Government provided major funding to support a residential and

commercial solar heating program. Congress also provided tax

credits to induce the use of solar systems. The credits

diminished with time, and when they disappeared, so did the solar

industry. Hence, the solar energy program ultimately failed

without the artificial financial supports that had been provided.

(As I write this, I understand that wind energy appears to have finally

become a financially competitive technology).

On a number of occasions,

members of Congress were asked by constituents where one could best

earn a Masters degree in solar energy. When such inquiries were

forwarded to me, I told the constituent to work instead toward a

Masters in Mechanical Engineering, and take electives related to solar

energy. I said that solar energy was not a field with a bright

future and they were better off earning a more basic engineering

degree. Time proved me right!

ERDA was abolished September 30,

1977, and the Department of Energy was established. I served for

a brief time in the geothermal energy program, and then transferred to

the uranium enrichment program in 1980. I ultimately became

responsible for managing development of the Advanced Gas Centrifuge

(AGC) for uranium enrichment. This was a short-lived

responsibility. A decision was made in 1985 to establish a

selection committee, responsible for picking the next generation

technology for enrichment. AGC was competed against the process

called Atomic Vapor Laser Isotope Separation (AVLIS). A $2

billion gas centrifuge plant had already been built in southern Ohio,

so a technology that existed was compared with a technology that merely

looked good on paper. However, key members of the selection

committee had previously managed AVLIS technologies, so the outcome was

preordained. AGC lost, and the existing centrifuge facility was

dismantled. AVLIS won, yet was never built and never proved what

it could do. So the enrichment program suffered a major failure

of purpose. At this point, I had enough. I had always

enjoyed working with young people, and decided to explore how I could

become a high school Physics teacher. This became possible in the

fall of 1986, so I retired from Government after a 33 year career.

In my new capacity as a teacher, I

observed some unique failures in the field of education. The most

notable related to a study of student self esteem. An educator in

the Superintendent’s office initiated a program to promote student self

esteem. This was conducted in a middle school that sent students

on to my high school. The heart of the process was to never give

a failing grade of “F”. Instead, the student would receive a

grade of “IP”, meaning “In Progress”. The outcome of this study

was creation of a student body that had exceedingly high self esteem,

but very poor study habits. Their rude awakening occurred when

they entered high school and began to receive failing grades.

Their self esteem was demolished and they were left floundering.

My colleagues told me that they could spot these students within the

first week, and could project that they would do poorly. From

this example, and others, I learned to suspect the quality of a PhD in

Education!

So, what did I learn about failure

during my working days? I learned the obvious, that deliberate

failures are recognized as sound engineering, for they define system

limitations. I learned that concealing a lack of progress or

hiding unexpected failures will ultimately backfire. This can

lead to project cancellation and/or the firing of persons

involved. And finally, I learned that management failures are

inexcusable. They indicate poor management skills and reflect

back on the perpetrator. Such failures can only hurt one's career.

Despite the above, both of my

careers were time well spent. With but one exception (a year

spent in the Nuclear Regulatory Commission), every one of my

assignments was productive and enjoyable. I can only hope that

other members of the Class of 1953 have had such varied and interesting

careers!